Early in the novel The Wolf’s Path: Ronin, Takeshi defeats several samurai while escaping from Yasuda village. How plausible are the feats described?

I wanted the protagonist, a living legend like Takeshi, to display skill at the very limit of human capability. Through Jiro’s eyes, we first learn the ronin’s reputation: a man wanted in several provinces by various families, with more than a hundred registered petitions of revenge against him. Someone who has assassinated over fifty samurai outside of duels and battles. And while telling is good, showing is even better, so his reputation gets put to the test within moments.

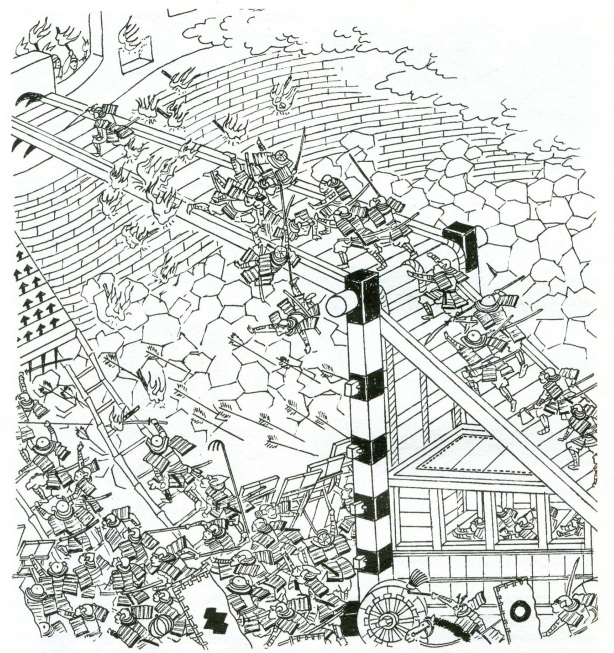

Jiro, the guard captain, orders his men to block the village exits through which Takeshi might flee, before ordering a coordinated spear attack. Four mounted samurai wait with bows, not under Jiro’s command, but having heard rumors that Takeshi was there and remaining on standby in case Jiro fails.

The ambush gets frustrated when four samurai, young and drunk, appear on the scene to provoke Takeshi, and he dispatches the three closest with a stroke from the scabbard (iai). Here we find the first scene that might challenge the limits of ability. Let’s see how it’s described:

Takeshi stood up, unimpressed at the assassins’ triumphant smiles. Then, with a circular motion, he unleashed a slash from the scabbard that opened the belly of the samurai before him. In the same fluid movement, he spun and ducked to avoid a blow from the man behind him. As the sword passed over his head, the ronin severed his adversary’s foot at the ankle and inflicted a deep wound across the torso of the enemy on his flank, throwing him to the ground. All in a single swing.

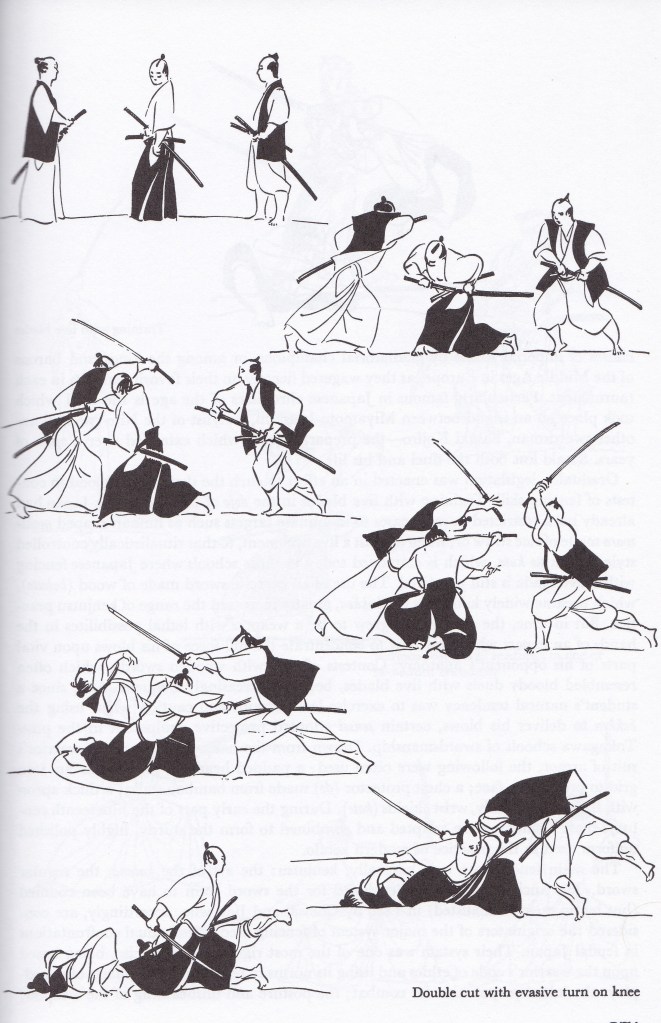

What Takeshi accomplished is a variant of the technique shown in this page from the book Secrets of the Samurai.

The difference is that it involves three enemies instead of two, but the concept remains the same. The most difficult part is cutting through an adversary’s foot, something that would depend on the katana’s quality and the force of the cut (aided by the spin). While the sequence of soft tissue-bone-soft tissue is plausible, it would require great precision, plus clumsiness on the samurai’s part, which in this case is justified by the fact that they’ve had too much to drink.

That some katanas possessed the power to amputate is reflected in the practice of testing katanas on corpses and criminals (something that also appears in the novel and which we’ll discuss in the future). For example, a katana from 1648 contains this description:

Sen’a tested this blade on a criminal and cut through a body via the standing kesa [diagonal across the body] cut and with ease down to the [height of the] shin.

After eliminating the three samurai, Takeshi cleans the blood from his sword with a sharp flick and sheathes it again. Abandoning his position, a young guard eager for glory appears on the scene and threatens Takeshi from behind, pointing his spear at him. Another scene where the ronin performs a new feat:

Takeshi pivoted, deflecting the spear with his elbow. Steel flashed as he drew his sword again, shattering the spear, severing the guard’s armored arm, and scattering fragments of sawdust after grazing the house wall.

Jiro stared at the ronin’s defiant stance as his enemy’s arm fell to the ground amid shards of metal, wood, and blood. The reckless young man slumped between the floor and wall, his shrieks mingling with the sobs of the earlier maimed samurai. A steep price to pay for pursuing his own glory.

The villagers’ screams snapped him from his stupor: the ronin was fleeing. He had taken the southern street, the narrower one.

As we’ve seen previously, a katana blow can sever an arm. In this case, the difficulty lies in breaking the spear and the armor. The key to success lies in the guards’ poor equipment, who we recall are described as “little more than armed peasants.” The wooden spear lacks metal reinforcement, and the arm can be cut at the point where the plates interlock, or even pierce them if they’re thin plates of poor quality, like those these guards would wear. Even then, it’s an extremely difficult action, but still within the realm of possibility.

The pursuit is thwarted by the chaos caused by the fleeing villagers, allowing Takeshi to dispatch a few enemies while approaching the exit. These fights don’t contain extraordinary elements, so I won’t delve into them. However, the last obstacle between him and the exit is a mounted samurai who shoots an arrow at him and then charges toward the ronin with his sword. Here’s how Takeshi faces him:

As the arrow took flight, Takeshi deflected it aside with an almost imperceptible movement and charged the rider, who discarded his bow and drew his sword. As he passed the rider, Takeshi swerved right to avoid the samurai’s attack and struck the horse’s ankles with the flat of his blade. The animal crashed to its knees with a thud before losing its balance and falling sideways, sending its rider tumbling across the ground. (…) Raising his sword overhead with both hands, he struck a blow that pierced the man’s helmet, cracked his skull and sent a spray of blood across Takeshi’s face.

This scene contains three elements that deserve closer analysis:

- Deflecting the arrow using the katana

- Making a horse stumble using the sword’s flat

- Piercing the helmet (and skull) with the katana

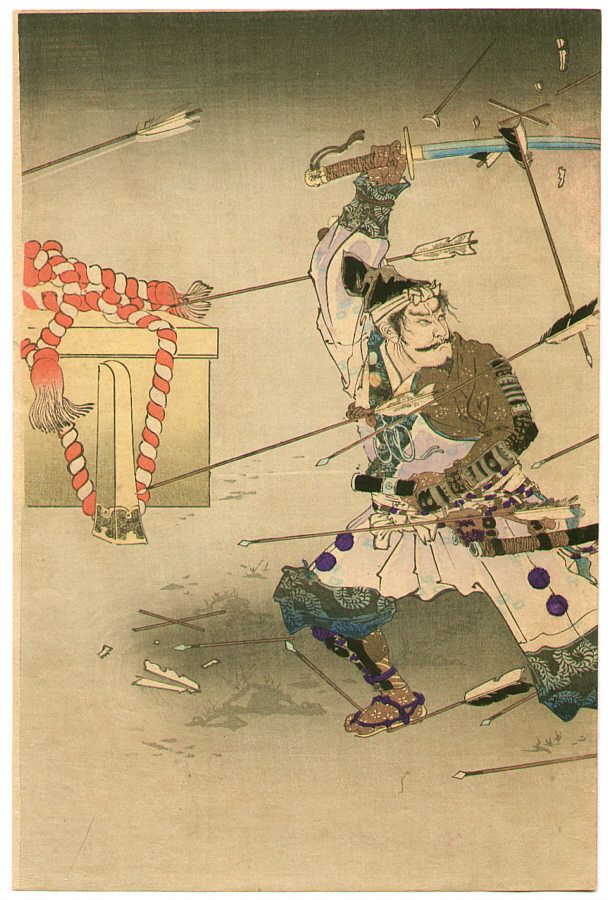

Deflecting arrows using the katana is documented in ancient sources, as shown in the illustration above, among others. The idea would be similar to the video I show below. Here it’s possible that the arrow’s speed isn’t as high as it would have been in the scene, but it conveys the idea. The fact that there are swordsmen capable of even cutting a bullet shows that deflecting an arrow isn’t so far-fetched in comparison.

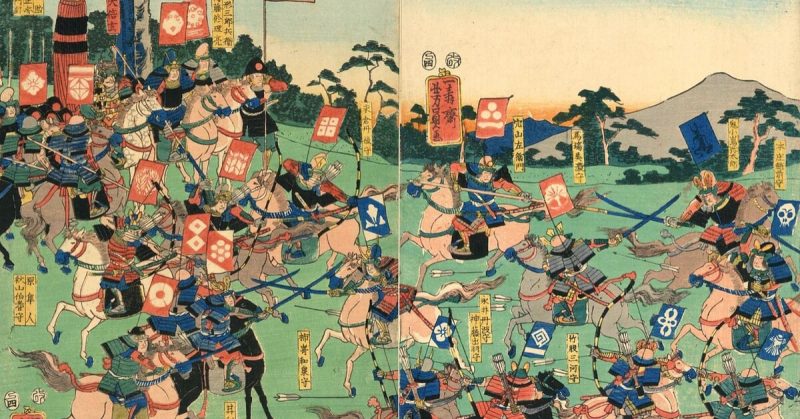

For the second point (making the horse stumble using the sword’s flat), there isn’t much information: period manuals reference attacks with polearms to cause horses to stumble, but there are no references to the katana using the blade’s flat. It’s possible to achieve if you strike at the moment when the horse lifts its leg. It would be extremely difficult, but not impossible. The horse would be stunned but barely injured, allowing Takeshi to later use it to escape.

As for the third point, piercing the helmet or kabuto is also documented. While this image was created in 1850, it describes the skill of Wakiya Yoshisuke, a 14th-century warrior, and it seems that in the Sengoku era this happened more than once. Although the cut isn’t as deep as in the illustration or the novel, you’ll find a video below that presents a similar cut.

The final action, when Takeshi raises the horse with a tug of the reins, is plausible with a mount trained for war conditions.

This entire scene serves to present the protagonist’s skills to the reader, in order to set the tone for his future feats. What’s interesting is that Takeshi’s favorite weapon isn’t the katana, but the naginata, with which he’s much more skilled. And surprisingly, there are at least three warriors throughout the novel with even greater ability.

While all of Takeshi’s actions exist at the limit of what a sword master can achieve, the complicated part is getting each and every one of these actions to work out perfectly. But that’s why Takeshi is a legend, and The Wolf’s Path: Ronin is a grimdark fiction novel and not a historical account.

Leave a comment