In writing this novel, I broke several rules that every aspiring writer hears from books, courses, and mentors. One of the big ones? Create a protagonist readers can easily relate to. Save the other types, they said, for when you’ve got more experience or a solid track record.

I almost centered the novel on a different character: Zasuro. He’s the hero of the story, after all: someone with a strong sense of duty and justice who wants to make the world a better place. It’s easy to root for him… and yet, he wasn’t the protagonist I wanted. I wanted the story told through someone who wasn’t the hero. I wanted a villain’s perspective.

That’s when I discovered Mark Lawrence’s Prince of Thorns. Here was a debut novel told entirely from a villain-protagonist’s point of view, and it was a huge success. That gave me back the confidence in my instincts that I never should have doubted. Done right, a villain-protagonist can absolutely carry a story. What matters isn’t so much that we connect with the protagonist, but that they’re fascinating to watch.

Now, readers can sympathize with Jorg’s tragic backstory. With Takeshi, it’s trickier. While his past is just as tragic (maybe more so) we only get glimpses. Like the fact that he was raised by a woman who wasn’t his mother, who found him as an infant trying to nurse from his dead mother’s breast, coughing on the blood that ran from her head to her chest. It’s a horrifying image, but we don’t even see it until halfway through the book.

I tackled this challenge from two angles. First, if Takeshi’s despicable actions made him impossible to relate to, I could at least make him impossible to ignore. I wanted readers thinking, “God, I hate this guy, but I have to know what he’s planning next.” Second, since I was using multiple POVs, characters like Zasuro could forge that emotional connection with readers while Takeshi established himself as a force in the story.

What surprised me was my beta readers’ feedback. They told me that as the novel progressed, they actually started rooting for Takeshi: cheering his victories and feeling bad about his losses. Surprising, yes, but not completely unexpected. Throughout the story, Takeshi reveals human qualities that, while they don’t redeem him, are genuinely admirable. For starters, he’s fearless: he’ll stare down death without blinking, regardless of whether his cause is noble or not. Combined with his feral nature (hence “the Wolf”), you could almost see his brutality as that of a predator who doesn’t think in terms of good or evil, just survival in a world where might makes right.

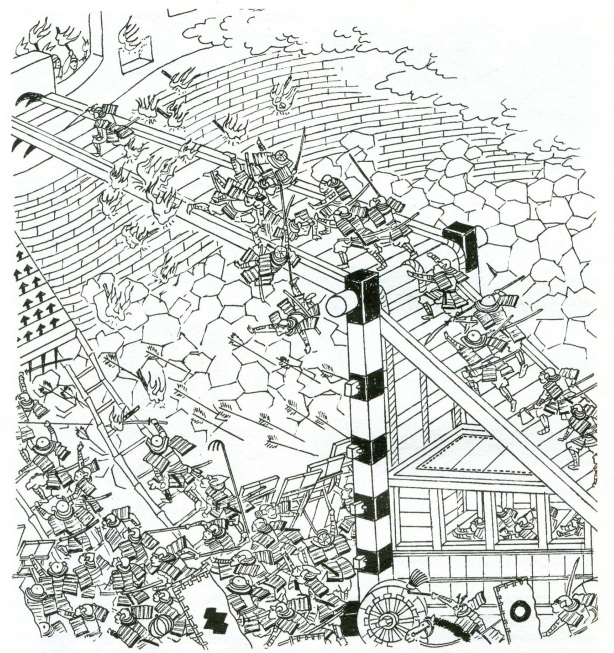

Right from chapter one, we see him take personal risks visiting Yasuda village, showing his men he won’t ask them to do anything he wouldn’t do himself (one of many parallels with Zasuro). And while he’s terrifying and cruel to outsiders, he never punishes his own people without cause. We watch him genuinely care about his soldiers’ well-being, both physical and mental, and he never leaves them behind in battle, even when retreat would be the smart move.

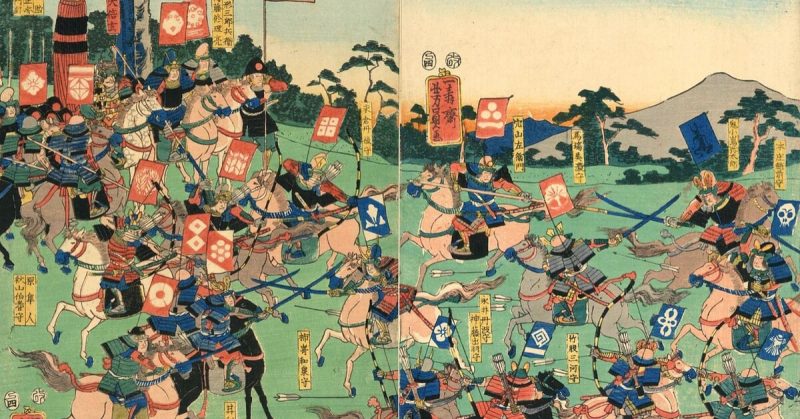

His merit-based recruitment might stem from pure pragmatism, but it shatters the era’s rigid hierarchies of class, age, gender, and birthplace. A woman named Kanako leads his cavalry simply because she’s proven herself the best. Not that Takeshi is some kind of progressive: he segregates men and women in camp and has no problem selling female captives to brothels.

Yet he has qualities that humanize him, like his protectiveness of his lover and daughter. But perhaps his most sympathetic moment comes when he develops an unwavering loyalty to Zasuro, channeling his violence in service of the prince. That desperate need to connect with someone he admires, to earn their approval: we’ve all felt that. Despite everything, we find ourselves wanting him to succeed.

His bond with Zasuro probably generates the most sympathy. We naturally identify with the hero, so when Zasuro is on the brink of death and we watch Takeshi risk everything to save him, we can’t help but admire his loyalty and courage even when we know, rationally, that he’s beyond redemption.

All that said, only a handful of people have read this story so far. Once The Wolf’s Path: Ronin hits shelves, we’ll see if my analysis holds up with a wider audience. I hope that Takeshi will prove to be the kind of complex protagonist who leaves readers conflicted, and more importantly, unable to stop turning pages.

Leave a reply to The Treatment of Non-Combatants in the Sengoku Era… and in the Novel – Robert Nakamura Cancel reply