In a cruel and ruthless world, Zasuro stands out with his unwavering sense of duty and justice: a ray of light cutting through the darkness. Numerous characters find themselves irresistibly drawn to this charismatic prince who grew up as a hostage among his enemies before returning to his people in a daring escape. He’s a man beloved by the people, admired by his troops, and respected even by his enemies.

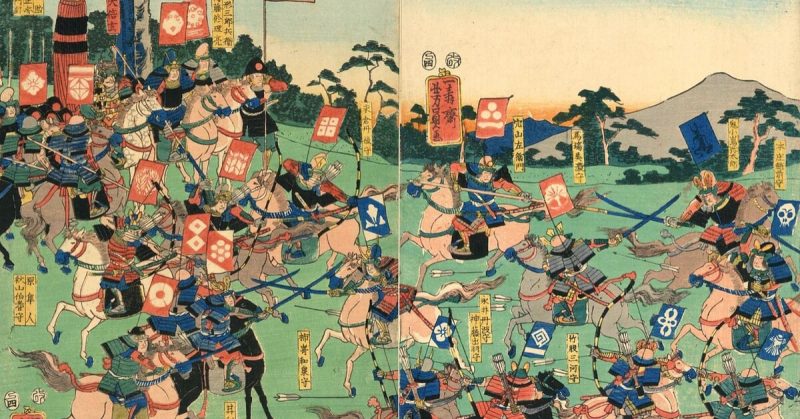

As a hero, he embodies numerous classic tropes: the meteor shower at his birth was interpreted by many as a divine sign that Zasuro was destined to reunify the empire. His vision for social reform, rooted in Confucian ideals, only strengthens this prophetic narrative. He’s a natural-born leader who never hesitates to fight alongside his men when the situation demands it, proving he won’t ask them to face dangers he wouldn’t face himself. In essence, he’s the archetypal hero. A hero… perhaps too perfect.

Zasuro isn’t actually a Japanese name at all: it’s a fantasy creation that merely sounds Japanese by design. An artificial name for an idealized hero, deliberately contrasting with the other characters who carry authentic, historical names.

Even novice writers understand that perfect characters become tedious. This was a risk I might have accepted since Zasuro isn’t this novel’s protagonist. However, I chose to weave in meaningful flaws and vulnerabilities because he serves as a POV character: one I expect readers will connect with most readily until our villainous protagonist Takeshi establishes his grip on the narrative. Without these imperfections, readers might reject both Takeshi for his cruelty and Zasuro for his impossible perfection, making these adjustments essential.

How do you craft a hero capable of serving as Takeshi’s moral counterpoint without making him insufferably flawless? My approach was to weaponize his virtues: turning his greatest strengths into liabilities in a world that demands ruthless pragmatism for survival. Excessive empathy becomes crippling when you must send soldiers into battles that guarantee casualties, even in victory, leaving him haunted by guilt and doubt.

While Zasuro can somewhat ease his conscience by fighting on the front lines (demonstrating he’ll face the same perils he asks of his men), his position forces him to take greater risks than other commanders. Years spent as a hostage among enemy clans have cast permanent shadows over his loyalty. He feels compelled to prove himself repeatedly, especially to his father the daimyo, with whom he shares a strained relationship. This dual burden (needing to prove his worthiness as heir while grappling with the cost in human lives) occasionally drives him toward decisions that result in tactical blunders and strategic failures.

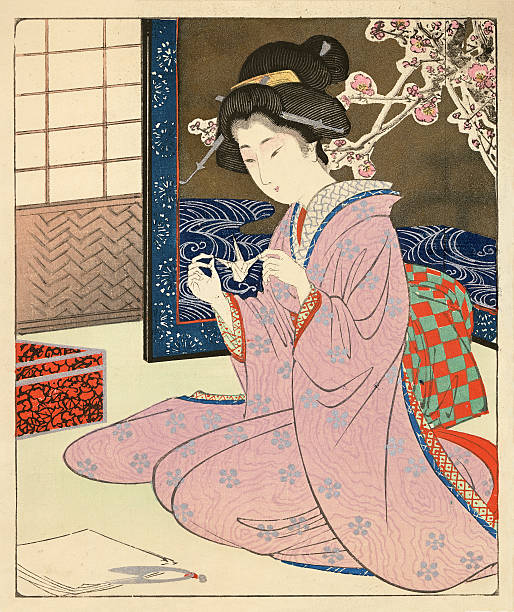

His troubles extend far beyond the battlefield. Political idealism (his reform agenda built on Confucian principles) creates powerful enemies who prefer the current order, ultimately culminating in an assassination attempt. Meanwhile, his romantic relationship with a servant named Okiku severely complicates his political standing when marriage proposals arrive from both court allies and enemy clans seeking peace through union. Time and again, the very qualities that should make him “perfect” become fatal flaws in navigating a world hostile to idealism.

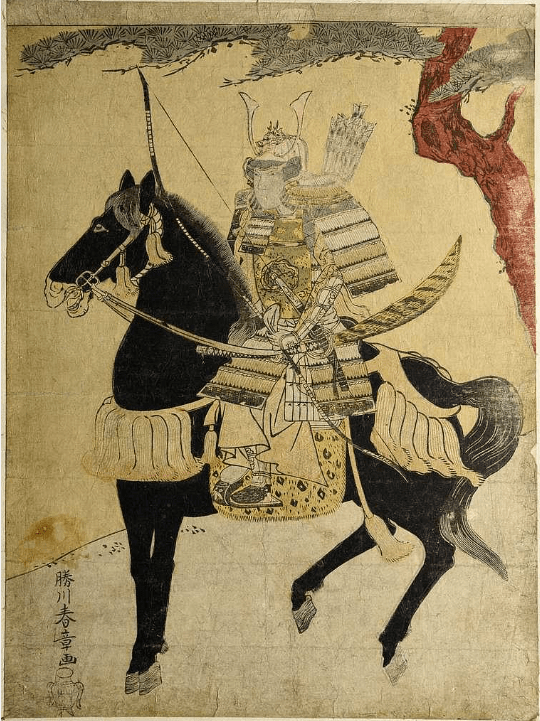

Known as “the Blue Dragon,” Zasuro’s epithet symbolizes spring, renewal, and fresh beginnings: his reforms would herald a new age for the empire. The title also evokes wisdom and strength. While his youth and skill in battle bring Minamoto Yoshitsune to mind, the character draws inspiration from a different figure in the Japanese epic Heike Monogatari: Taira Shigemori, the “prudent minister”. Like Zasuro, Shigemori possesses deep moral convictions and sense of duty while maintaining a troubled relationship with his father Taira Kiyomori, a merciless ruler who values nothing but raw power, and stands up to his despotic rule.

Though Zasuro as our hero remains central to every major plot development, this analysis wouldn’t be complete without examining his relationship with our true protagonist: Takeshi.

Initially, Zasuro resents his father’s decision to recruit a notorious assassin band to supplement their forces. But fate (or perhaps authorial design) places him in Takeshi’s debt when the ronin leader saves his life from internal enemies. Soon Zasuro finds himself captivated by this unconventional warrior and his unique code of honor. He decides to make Takeshi the proving ground for his ideals: if he can transform a ruthless killer into an honorable samurai, it would validate his Confucian belief that virtue matters more than bloodline. What begins as a political experiment, however, evolves into genuine brotherhood forged in battle’s crucible. And once more, his capacity for empathy will exact a terrible price.

Zasuro is a hero, the classic fairy-tale prince, as good-hearted as he is skilled in combat. But the world around him ends up turning his virtues into obstacles difficult to overcome. In The Wolf’s Path: Ronin, we’ll see whether this hero overcomes the challenges he faces, succumbs to them before surrendering his ideals, or adapts to the world around him, transforming into a more ruthless and pragmatic leader.

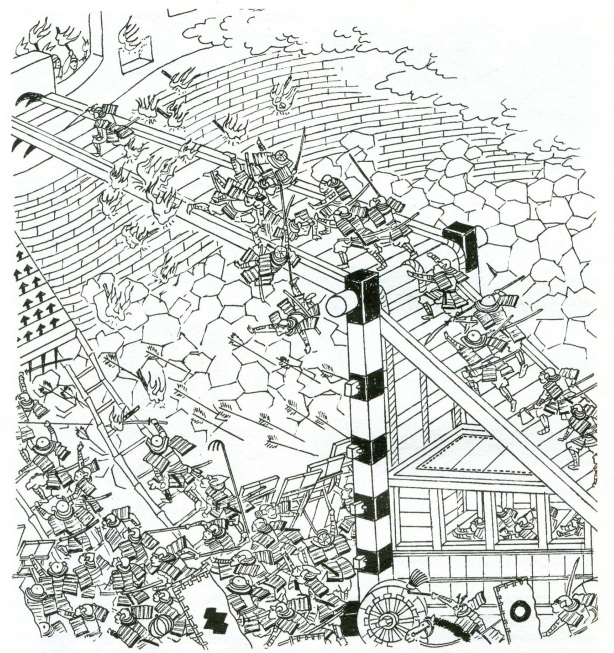

Leave a reply to Siege Weapons and Equipment in the Sengoku Era… and in the Novel – Robert Nakamura Cancel reply