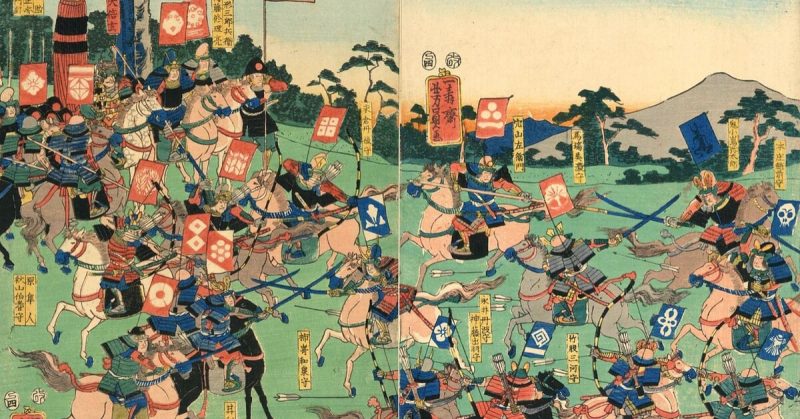

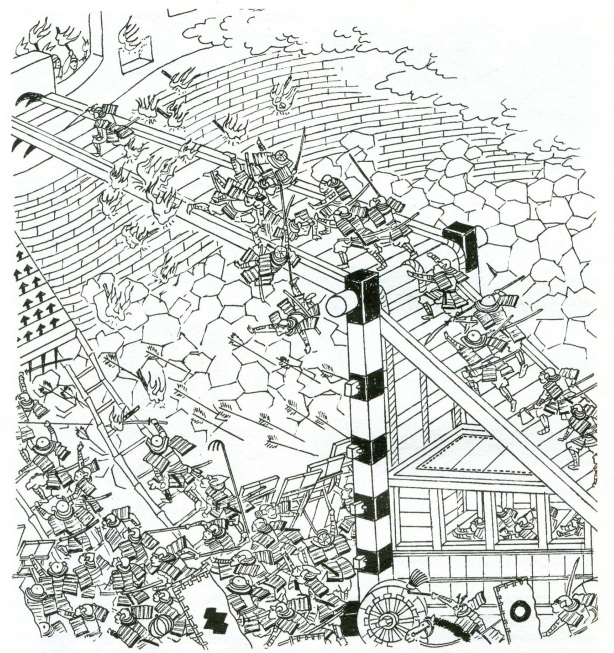

Comprising hundreds of well-equipped ronin and even including a cavalry unit, the band led by Takeshi the Wolf would have been an anomaly during the Sengoku period. While bandit groups with horses did exist, their numbers (from what I’ve been able to research) never reached such heights. The closest historical precedent would be the “Wildcats.” During the siege of Osaka (1614-1615), some sources estimate that as many as 4,000 ronin joined Hideyori’s forces, though these warriors formed no unified group and had no leader beyond the samurai who commanded them: they earned the name “Wildcats” only after joining the defenders.

Nevertheless, the existence of a ronin band like Takeshi’s, while historically hard to verify, becomes plausible in a world where entire clans could vanish overnight, creating masses of masterless warriors eager to sell their swords in hopes of achieving samurai status.

Takeshi’s inclusion of cavalry, spearmen, swordsmen, spies, and non-combatants (including women) for logistical support stems less from deliberate planning than from his policy of accepting anyone with useful skills (not necessarily martial ones). He didn’t design his band around specific numbers of archers or horsemen; rather, he organized them based on whatever personnel he happened to have at any given time. As ronin, they lack the wealth to purchase equipment outright, but the battlefields of an era marked by civil war could supply them with whatever they needed.

Given how provocative and blasphemous their name is (invoking divine protection while debasing that connection by linking it to an unclean animal) why call themselves the Hachiman Dogs? Such a name clearly places them beyond the pale of law and conventional honor codes; they certainly wouldn’t use it when negotiating with local daimyo, who might otherwise turn a blind eye in a world where samurai and warrior monks clash all too frequently.

A reader’s first instinct might be that, since Hachiman serves as the patron deity of warriors, this represents a way of calling themselves “dogs of war.” In this sense, they’d resemble a European mercenary company more than anything else. However, the name actually references the Hakkenden, which tells the story of a warrior group known as the “Eight Dogs.” Since Hachiman contains the character for “eight” (originally meaning “eight banners”), and the band’s named warriors also number eight, it seemed fitting (although they do not embody the eight Confucian virtues by any means). The story of how a curse was supposed to make Satomi Yoshizane’s descendants “depraved as dogs” and the later resolution (when their birth carries the potential for virtue) also reflects the changes affecting the band throughout the novel, particularly those of its leader.

The band’s name serves a dual purpose: easily recognizable as a mercenary group to readers unfamiliar with these cultural references, while offering deeper meaning to those versed in Japanese literature and mythology.

Due to their limited numbers, Takeshi’s ronin cannot challenge an entire samurai clan, but their activities significantly impact various plot threads: from village raids to their service under the Asaka clan, not to mention their blood feud with the mysterious sect known as the Circle of Black Jade.

Throughout the novel, we’ll discover whether the Hachiman Dogs achieve samurai status, remain outlaws, or meet their end at the hands of the forces drawing them into the empire’s power struggles.

Leave a comment